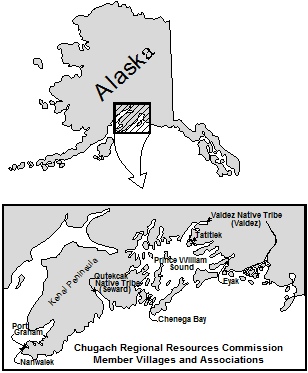

The Chugach Regional Resource Commission (CRRC) is an Alaska Native Tribal consortium in south-central Alaska whose Dena’ina, Alutiiq, and Sugpiaq villages and association members have stewarded of the Kachemak Bay watershed for over 10,000 years. CRRC’s mission is to promote Tribal sovereignty and protect subsistence lifestyles through the development and implementation of Tribal natural resource management programs to assure conservation and sustainable economic development in the traditional use area of the Chugach Region.

CRRC serves the greater Chugach region of Southcentral Alaska, including Lower Cook Inlet, Resurrection Bay, and Prince William Sound. Within Lower Cook Inlet CRRC will work with area member tribes to establish the Kachemak Bay Watershed Collaborative (Collaborative or KBWC) to protect salmon streams located within the Kachemak Bay Watershed (Watershed). The Athabascan and Sugpiaq communities located within the Watershed rely on a subsistence economy, as they have since time immemorial.

CRRC will engage a diverse group of stakeholders with land ownership or authority within the Watershed, including Federally recognized Tribal entities, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Alaska Departments of Natural Resources and Fish and Game, the municipalities of Homer, Kachemak Selo, Voznesenka and Razdolna, Seldovia and the unincorporated Native village communities of Nanwalek and Port Graham, and conservation organizations.

Many changes related to warming fresh and marine water temperatures impact the subsistence resources. Increasingly common drought conditions and spruce beetle outbreaks in the region threaten the health of the plants and animals rural communities rely upon for subsistence. These changes are happening at a rate no one thought possible even a decade ago. Land management activity within the Watershed can exacerbate such impacts. The Collaborative will work to be more inclusive of tribal and other local communities along with local, state, and federal stakeholders in monitoring, planning, and decision-making within the Watershed. The implementation of risk assessments and planning documents, along with preserving connectivity and non-climate stressor mitigation actions, will ensure better protection and management of salmon habitat in the Watershed.

Project location

The 4,926,794-acre Watershed is made up of five small watersheds located in the Kenai Peninsula Borough within the state of Alaska and encompasses the municipalities of Homer, Kachemak Selo, Voznesenka, Razdolna, Seldovia, and the unincorporated Alaska Native village communities of Nanwalek and Port Graham. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) Hydrologic Unit Codes (HUC) in which the group will work are: Cook Inlet, Stariski Creek-Frontal Cook Inlet, Fox River, Sheep Creek and Quiet Creek-Frontal Kachemak Bay Watershed HUC ID #s: 1902080000, 1902030108, 1902030110, 1902030109 and 1902030111 respectively.

Technical project description

There is currently is no group focused specifically on this Watershed, although a diverse array of stakeholders, including livestock grazers, tourist and recreation groups, industry, environmental organizations, recreation advocates, universities, land use, tribal, state and federal entities, municipalities and the general public utilize the area. This Watershed group will also help fill a planning gap left by the elimination of Alaska’s Coastal Zone Management program.

There are several ongoing or previous watershed planning activities, projects, or efforts related to the Watershed that the Collaborative will build upon, including:

- The Kachemak Bay Fox-River Climate Risk Assessment analyzes current threats to salmon habitat within a portion of the Watershed, addresses salmon habitat connectivity and climate resiliency for the entire Watershed, and works with federal and state resource agencies to enter into cooperative agreements for management of salmon habitat on a watershed basis;

- The Alaska Department of Fish and Game Fox River Flats Critical Habitat Area (FRFCHA) management plan addresses regulatory management goals for the FRFCHA and includes managing the area to 1) maintain and enhance fish and wildlife populations and their habitat; 2) minimize the degradation and loss of habitat values due to fragmentation, and; 3) recognize cumulative impacts when considering effects of small incremental developments and action affecting critical habitat resources.

- The Kachemak Heritage Land Trust’s (KHLT) Krishna Venta Conservation Management Plan addresses working collaboratively with state, federal, and local entities as KHLT purchases and negotiates conservation easements on private lands for the purposes of management and protection of fish and wildlife habitat of KHLT’s 160 acres in the FRFCHA;

- The Kenai Mountains To Sea – Land Conservation Strategy to Sustain Our Way of Life on the Kenai Peninsula calls for the creation of contiguous “green” corridors along 20 inter-jurisdictional anadromous streams, most of which originate on the Kenai Refuge. Such protection will increase the resiliency of these streams and the marine habitat into which they feed from the effects of a rapidly warming climate while ensuring that large piscivores such as brown bears and wolves persist to transport marine derived nutrients onto the landscape;

- The Department of Natural Resources’ Kachemak Bay State Park and Kachemak Bay State Wilderness Park Management Plan addresses management of the 371,000- acre Kachemak Bay State Park and Kachemak Bay State Wilderness Park (State Park);

- The Cook Inlet Keeper State of the Inlet watershed restoration plan within the Watershed captures threats and community-specific concerns and ideas to help direct CIK’s watershed-based organization as the plan future projects.

Join the Collaborative:

If you are a federal, state, or tribal entity, conservation group, or anyone else interested in the welfare and sustainability of Kachemak Bay, please join our Collaborative. If you have any questions please contact Hal Shepherd halshepherdwpc@gmail.com